In 822 AD the Abbot Adelard instituted a parchment maker among the officers of his Abbey of Corbie in northern France.

The preparation of parchment is a slow and laborious and complicated process. The skin was washed in clear cold running water for a day and a half. It might be laid in the sun to help it rot and the hair fall out. Often the skins are soaked in wooden or stone vats in lime and water from 3-10 days, scooped out and draped hair side out over a great curved upright shield of wood.

The parchment maker stands and scrapes away the hair with a long curved knife. The bare skin , wet and dripping, is flipped over and scraped away again (must have been VERY fragrant by this time) it requires a surprising delicacy of touch and experience, not to pierce thru the skin, it is rinsed for two days more and stretched on a frame.

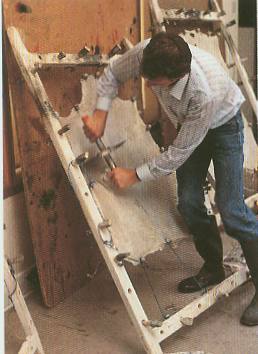

Here a modern parchment maker stretches and tightens the skin on a frame.

It's tied to the frame and little stones are put in the ends till it resembles a vertical trampoline. any cuts as it shrinks may result in holes in the end product:

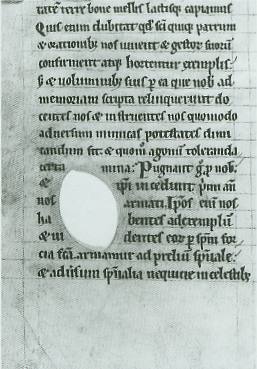

Here, an original manuscript is shown with a hole, these seem to occur especially in monastic manuscripts, since they could not afford or did not care for the luxury of rejecting sheets damaged. Here in a late 12th c manuscript the scribe has carefully written his text around the hole.

Here, an original manuscript is shown with a hole, these seem to occur especially in monastic manuscripts, since they could not afford or did not care for the luxury of rejecting sheets damaged. Here in a late 12th c manuscript the scribe has carefully written his text around the hole.

As the skin dries the scraping continues and the screws are tightened. When it is dry the scraping and shaving begin again. Here is a monk using the particular curved knife (called lunellum, little moon) for these last steps.

As the skin dries the scraping continues and the screws are tightened. When it is dry the scraping and shaving begin again. Here is a monk using the particular curved knife (called lunellum, little moon) for these last steps.

When the parchment has reached the desired thinness (by the 13th Century it approached tissue proportions) it is released and rolled up and stored or taken to be sold. Here a monk inspects a sheet of parchment from a parchment maker, you can see the curved knife and stretched wooden fame below.

When the parchment has reached the desired thinness (by the 13th Century it approached tissue proportions) it is released and rolled up and stored or taken to be sold. Here a monk inspects a sheet of parchment from a parchment maker, you can see the curved knife and stretched wooden fame below.

Apparently it was a well paid craft, meticulously documented. The accounts of the Sainte-Chappelle in Paris include the expenses in 1298 of a huge quantity of 972 skins at the cost of 194 livres and 18 sous, working out to 3 sous a skin, a considerable sum, plus more for the scraping and more for the man who selected them.

Parchment is extraordinarily durable, far more so than leather. It can last for a thousand years or more, in perfect condition. Good parchment is soft and thin and velvety and folds easily.

The grain side of the sheet, where the hair once was is usually darker in colour, creamy or yellow. The grain side too, tends to curl in on itself.